Bannockburn House ©Bannockburn House Trust, 2018 – kindly donated by Alistair Thomson

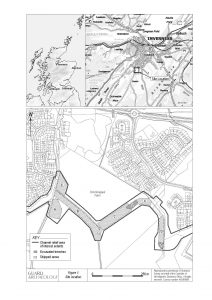

The first survey of a potential site for the Jacobite army camp shortly before the battle of Falkirk is planned for the weekend of 3rd-5th August 2018.

In the summer of 1745, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, commonly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, arrived in Scotland to raise an army and march towards England to reclaim the throne. On his way south, Charles spent the night of the 14th of September at Bannockburn House near Stirling.

It seems likely that there was a reason that Charles stayed at Bannockburn; perhaps the army command or the Prince himself was aware of the support of the house’s owner Hugh Paterson to the Jacobite cause, or perhaps he had met him in exile in the years after the 1715 rising. It is also possible that the selection of Bannockburn was solely for its practical location, near the road to Edinburgh.

In early January 1746, Charles returned to Bannockburn House following the retreat of the Jacobite army from England. Located so close to Stirling, this mansion made for ideal headquarters for the prince and his staff to prepare for the siege of Stirling.

Even though the city surrendered on January 8th 1746, the attempts of the Jacobite army to take Stirling Castle were unsuccessful. Meanwhile, the Hanoverian army, tasked with bringing the Jacobite army to battle, marched from Edinburgh to Falkirk, planning to advance on Stirling.

Contemporary drawing of Jacobite and Hanoverian soldiers from the Penicuik Collection

The Jacobite army set out to meet the Government forces. Although the ensuing battle on 17th January was a victory for the Jacobites, it was clumsy and unsatisfying and marked the beginning of the downturn in their fortunes, which culminated in their defeat at the battle of Culloden on 16 April 1746. The Hanoverian victory resulted in the banning of tartan and the suppression of Gaelic culture across Scotland.

During the Jacobite siege of Stirling, Charles became ill, and he was nursed by Clementine Walkinshaw, the niece of Hugh Paterson, at Bannockburn House. She became the mistress of the Prince and followed him into exile in France in 1752, where they had a daughter Charlotte in 1753, the Prince’s only recognised child. The house itself became forfeit following the defeat of the Jacobite cause.

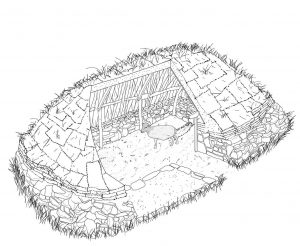

Contemporary drawing of a Jacobite army camp, from the Penicuik Collection

It is thought that some of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s troops camped in the grounds of Bannockburn House. For the first time an organised archaeological survey is planned, by the Community Trust that bought the seventeenth century house and its grounds in late 2017.

‘We hope to establish the location of the camp and to find examples of both daily camp life such as cooking utensils and of the equipment men and horses would have used in battle,’ said Willie McEwan Vice-Chair of Bannockburn House Trust.

View of field where the Jacobite army camp may have been located ©Bannockburn House Trust, 2018

Archaeologists from GUARD Archaeology Ltd will guide metal detectorists and diggers in carrying out the archaeological investigations. Volunteers are invited to come along and help with the archaeological survey of this site, which is adjacent to Bannockburn House. Click here for details and how to apply for a place or here to support the work. This is a unique and exciting opportunity to try and resolve the mystery of where the Jacobite army camped in January 1746 before marching to the battle of Falkirk.

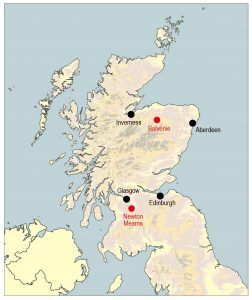

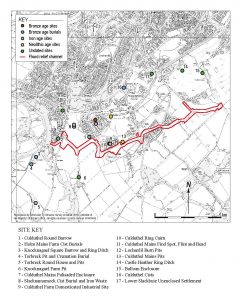

Recently published research from two sites at opposite ends of Scotland reveals new evidence for Bronze and Iron Age landscapes.

Recently published research from two sites at opposite ends of Scotland reveals new evidence for Bronze and Iron Age landscapes.

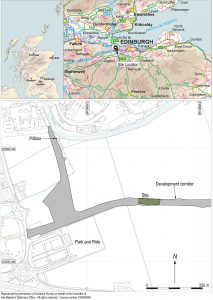

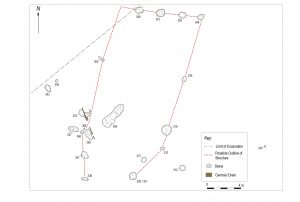

Recently published research by Bob Will of GUARD Archaeology reveals the discovery of the complex history of settlement at a place in the Lothians of Scotland, from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age and Iron Age into the early medieval period.

Recently published research by Bob Will of GUARD Archaeology reveals the discovery of the complex history of settlement at a place in the Lothians of Scotland, from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age and Iron Age into the early medieval period.

Two truncated roundhouses near the north end of the site were dated to the Iron Age. An associated fragment of a miniature quern was recovered; these tend to be found in the east of Scotland during the Iron Age. The final phase of activity on-site comprised the remains of two corn-drying kilns, dated to between the sixth and eighth centuries AD, that survived as oval pits containing considerable quantities of burnt and charred cereal grains. Associated with the better-preserved kiln was a rim sherd of coarse pottery and two fragments from a rough quern.

Two truncated roundhouses near the north end of the site were dated to the Iron Age. An associated fragment of a miniature quern was recovered; these tend to be found in the east of Scotland during the Iron Age. The final phase of activity on-site comprised the remains of two corn-drying kilns, dated to between the sixth and eighth centuries AD, that survived as oval pits containing considerable quantities of burnt and charred cereal grains. Associated with the better-preserved kiln was a rim sherd of coarse pottery and two fragments from a rough quern. While the archaeological investigations provided evidence for occupation of this place over a long period of time, it was surprising that little evidence for settlement from the Roman occupation of southern Scotland was encountered, considering the presence nearby of a Roman fort, milestone and temporary camps. The archaeological remains from the excavation nevertheless provide a palimpsest of prehistoric and early medieval occupation and support similar occupation and settlement evidence from the wider region. The early medieval date for the corn-drying kilns provides direct evidence for settlement and agriculture, as well as a domestic setting for the long-cist cemetery at Catstane to the north. Together with another nearby long-cist cemetery to the south and contemporary field boundaries near Gogar Church, the results are combining to gradually fill out a picture of sustained settlement and agriculture in this area of the Lothians during the early medieval period.

While the archaeological investigations provided evidence for occupation of this place over a long period of time, it was surprising that little evidence for settlement from the Roman occupation of southern Scotland was encountered, considering the presence nearby of a Roman fort, milestone and temporary camps. The archaeological remains from the excavation nevertheless provide a palimpsest of prehistoric and early medieval occupation and support similar occupation and settlement evidence from the wider region. The early medieval date for the corn-drying kilns provides direct evidence for settlement and agriculture, as well as a domestic setting for the long-cist cemetery at Catstane to the north. Together with another nearby long-cist cemetery to the south and contemporary field boundaries near Gogar Church, the results are combining to gradually fill out a picture of sustained settlement and agriculture in this area of the Lothians during the early medieval period. Recently published research reveals a range of artefacts recovered from two sites on the edge of the medieval burgh and castle at Stirling.

Recently published research reveals a range of artefacts recovered from two sites on the edge of the medieval burgh and castle at Stirling. This section of footpath runs behind Cowane’s Hospital next to the Church of the Holy Rude and on the perceived line of the Stirling town wall, which was constructed sometime in the sixteenth century.

This section of footpath runs behind Cowane’s Hospital next to the Church of the Holy Rude and on the perceived line of the Stirling town wall, which was constructed sometime in the sixteenth century. One of the more unusual artefacts to be recovered from the Back Walk was a WWI military belt buckle. The military buckle is from the Austrian army and has the double headed imperial eagle and the Austrian coat of arms and is one that was standard issue during WWI.

One of the more unusual artefacts to be recovered from the Back Walk was a WWI military belt buckle. The military buckle is from the Austrian army and has the double headed imperial eagle and the Austrian coat of arms and is one that was standard issue during WWI. The results of one of GUARD Archaeology’s community archaeology projects, undertaken with the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society has been nominated in the

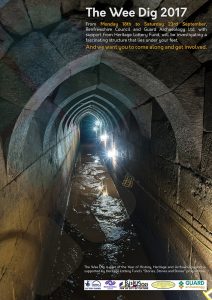

The results of one of GUARD Archaeology’s community archaeology projects, undertaken with the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society has been nominated in the

Up until this time, during the earlier Mesolithic period (c. 8000-4000 BC), Scotland was inhabited by small groups of hunter gatherers, who led a nomadic lifestyle living off the land. The individuals that built this Neolithic house were some of the earliest communities in Ayrshire to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, clearing areas of forest to establish farms, growing crops such as wheat and barley and raising livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs.

Up until this time, during the earlier Mesolithic period (c. 8000-4000 BC), Scotland was inhabited by small groups of hunter gatherers, who led a nomadic lifestyle living off the land. The individuals that built this Neolithic house were some of the earliest communities in Ayrshire to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, clearing areas of forest to establish farms, growing crops such as wheat and barley and raising livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs.

Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology has revealed the complex history of a turf and stone-built medieval building. Sherds of pottery obtained from the floor of the structure suggest it was in use during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. However, its construction is similar to other excavated buildings dated to the early medieval period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from several features and deposits ranged from the Bronze Age, through the Iron Age to the medieval period. The structure is an uncommon survivor of medieval rural settlement that is rarely excavated in Scottish archaeology.

Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology has revealed the complex history of a turf and stone-built medieval building. Sherds of pottery obtained from the floor of the structure suggest it was in use during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. However, its construction is similar to other excavated buildings dated to the early medieval period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from several features and deposits ranged from the Bronze Age, through the Iron Age to the medieval period. The structure is an uncommon survivor of medieval rural settlement that is rarely excavated in Scottish archaeology. The rareness of the Kintore medieval building is predominantly due to the lack of identification of them in the landscape, the result of their construction using perishable materials such as clay and turf, and changes in land-use which have led to their destruction. Often the stones from these buildings have been systematically removed over time, or the buildings replaced with new structures, or adapted to different uses. The survival of the Kintore building, despite being partially damaged and robbed, might be due to the marginal nature of the ground it sits on, which is very boggy in places and contains a large amount of stone, both above and below ground, which inhibited ploughing that might otherwise have removed all traces of the building.

The rareness of the Kintore medieval building is predominantly due to the lack of identification of them in the landscape, the result of their construction using perishable materials such as clay and turf, and changes in land-use which have led to their destruction. Often the stones from these buildings have been systematically removed over time, or the buildings replaced with new structures, or adapted to different uses. The survival of the Kintore building, despite being partially damaged and robbed, might be due to the marginal nature of the ground it sits on, which is very boggy in places and contains a large amount of stone, both above and below ground, which inhibited ploughing that might otherwise have removed all traces of the building. Better preserved medieval buildings, such as at Pitcarmick in Perthshire, retain clear divisions between a living end containing a hearth, and byre end with a central drainage slot. No such internal arrangements were apparent at Kintore but soil micromorphology analysis of the soils within the building suggest that there were differences between floor deposits at either end. The west end was associated with domestic activities and the east end was richer in livestock dung, which may indicate the internal division of the house. While there was no central drain within the byre east end of the building, this lay at a lower level than the west end, with the slope aiding drainage if animals were housed there.

Better preserved medieval buildings, such as at Pitcarmick in Perthshire, retain clear divisions between a living end containing a hearth, and byre end with a central drainage slot. No such internal arrangements were apparent at Kintore but soil micromorphology analysis of the soils within the building suggest that there were differences between floor deposits at either end. The west end was associated with domestic activities and the east end was richer in livestock dung, which may indicate the internal division of the house. While there was no central drain within the byre east end of the building, this lay at a lower level than the west end, with the slope aiding drainage if animals were housed there.