A new publication reveals the remains of a significant early Neolithic settlement that GUARD Archaeologists discovered, a focal point for where Scotland’s first farming communities gathered for large scale festivities.

The discovery was made during archaeological excavations undertaken by GUARD Archaeology prior to the building of new football pitches near Carnoustie High School.

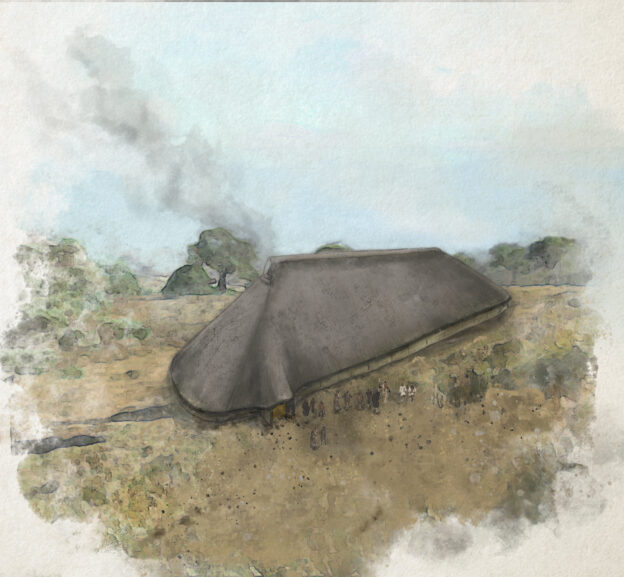

The Carnoustie excavation produced exceptional results, the traces of the largest early Neolithic timber hall ever discovered in Scotland dating from near 4000 BC. This was a permanent structure 35m long and 9m wide, built of oak with opposed doorways near one end of the building. Its large roof was supported by paired massive timber posts. Its walls were wattle and daub panels supported by posts that were partly protected by its over-hanging roof. And its internal space was sub-divided by more postholes and narrow channels marking partitions.

This monumental timber hall, completely alien to the culture and landscape of the preceding Mesolithic era, was erected by one of the very first groups of farmers to colonise Scotland, in a clearing within the remains of natural woodland. It was fully formed, architecturally sophisticated, large, complex, and required skills of design, planning, execution and carpentry.

But what makes this exceptional is that unlike other Neolithic halls in Scotland, which were all discrete solitary structures within the virgin farmland of early Neolithic Scotland, a smaller companion timber hall existed alongside the large Carnoustie Hall. This was still a substantial structure almost 20m long and over 8m wide.

While GUARD’s excavation of the smaller hall revealed a large hearth with charred cereal grains and hazel nutshells consistent with a domestic function, in contrast the excavation of the larger hall yielded evidence for the deliberate deposition of stone artefacts, tantalising traces of the beliefs and rituals of the community that built and used it.

The Carnoustie halls, elevated and prominent in the landscape, were probably close to routeways where people may have congregated naturally at various seasons of the year. The availability of hazel nuts in autumn is a strong indicator that that season was an important one for meeting, feasting and celebrating. The Carnoustie timber halls may have been a focal point, their significance great enough to attract interest from people from a much wider area. We know from the materials found in the Carnoustie buildings that some artefacts came from distant places and represent deliberate deposition, such as fragments of Arran pitchstone, an axe of garnet-albite-schist and a piece of smoky quartz from the Highlands, while other materials were found more locally such as agate, quartz and chalcedony.

After about 200 years, the halls were dismantled and a smaller hall built within the footprint of the larger hall around 3800-3700 BC, but this too continued to receive deliberate deposits of stone tools until about 3600 BC. The site continued to be revisited with evidence of people camping and gathering outside where the buildings once stood, carrying on the seasonal round of activities until around 2500 BC.

This was not the only prehistoric secret that the Carnoustie excavations unearthed.

A rare and well-preserved metalwork hoard of a sword within its wooden scabbard, a spearhead with a gold decorative band around its socket and a bronze sunflower-headed swan’s neck pin were found wrapped in the remains of woollen cloth and sheep-skin. This small hoard had been deliberately buried in a pit within the midst of a late Bronze Age settlement sometime between 1118 – 924 BC.

For around 1400 BC, during the Bronze Age, people had returned to this same site at Carnoustie, probably oblivious to its significance to earlier Neolithic communities. A settlement was established here, comprising a single roundhouse, much smaller than the previous Neolithic halls, and replaced three or more times over the following centuries until around 800 BC.

The best preserved of these Bronze Age roundhouses was positioned over part of the foundations of the large Neolithic timber hall. Like the other buildings it had an entrance facing south-east and during the course of its life it was used as a domestic dwelling, a workshop and also a byre. The overwintering and stalling of domestic livestock within buildings of this period seem to have been a common occurrence. Near this building, the hoard of precious weapons and jewellery was deliberately buried.

The metallurgical and lead isotope studies suggest that all the bronze objects were probably made in Scotland, but from metal imported from further south, eastern England for the bronze and, perhaps the Irish Sea area for the gold. If any object was a direct import, it would be the sunflower pin. The sword was a viable weapon that from the pattern of notches and rebound marks along its blades had probably seen some use in combat, but there was weakness in the core of the spearhead that would have made it vulnerable in use.

And while the metalwork in the Carnoustie Hoard was impressive enough, the associated organic remains are exceptional. The remarkable preservation of the wooden scabbard, woollen cloth and sheepskin was down to the anti-microbial properties of copper, which all of these items were in contact with.

This rich hoard of metalwork, together with a shale bangle found in the roundhouse indicate that while the settlement was otherwise very modest and unassuming, its occupants were wealthy and had some status in the wider community. Hoards such as this are rare, but a similar hoard of bronze swords and another gold decorated spearhead found in the 1960s just north of Dundee indicates a shared cultural practice amongst late Bronze Age households for burying wealth such as this for safekeeping. The reason as to why they never came back to recover these prized belongings, however, has been lost to the passage of time.

The last occupant of the Carnoustie site was a small field mouse – investigation of the contents of the spearhead’s socket revealed a considerable amount of fresh-looking grass stems stained by the copper, suggesting that a very small rodent (such as a field mouse) had set up house during the fairly recent past in the socket itself.

The archaeological work was funded by Angus Council and was required as a condition of planning consent by Angus Council who are advised on archaeological matters by the Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service, who considered there to be a potential for hitherto unknown archaeology to be buried at the site due to the proximity of known prehistoric archaeology.

ARO60: Neolithic timber halls and a Bronze Age settlement with hoard at Carnoustie, Angus by Beverley Ballin Smith, Alan Hunter Blair and Warren Bailie is freely available to download from Archaeology Reports Online.