Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology reveals how a rare enamelled Roman brooch provides insight into how the local Britons of south-west Scotland interacted with the Roman army during the late second century AD.

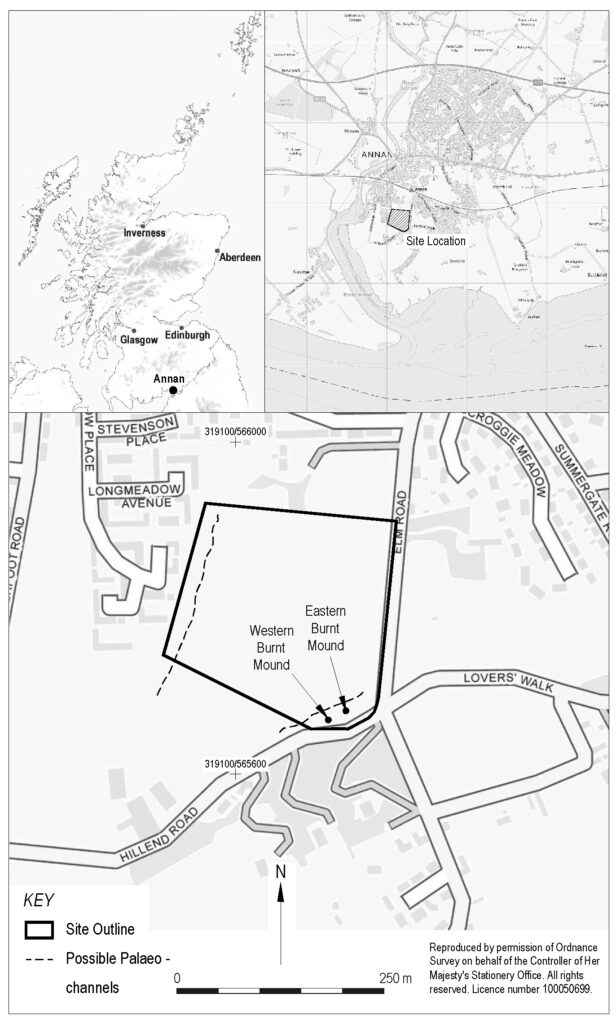

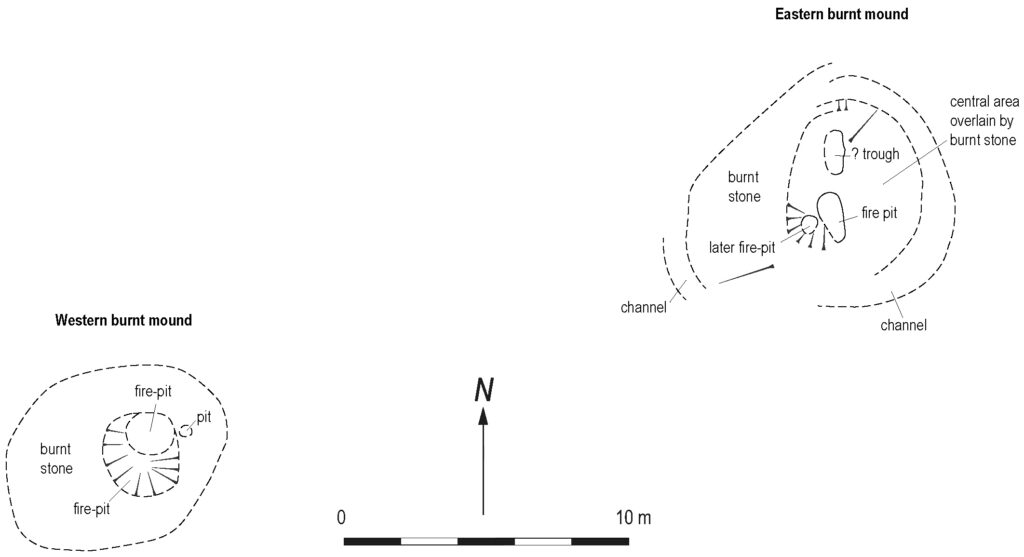

Excavations undertaken at William Grant & Sons Girvan Distillery at the Curragh in South Ayrshire in 2020 uncovered an Iron Age settlement dating to a period when southern Scotland had slipped from the grasp of the Roman Empire. The team of GUARD Archaeologists discovered the remains of what had once been a substantial timber roundhouse surrounded by a stout wooden palisade, with a large gated entranceway, likely the dwelling of a wealthy farming household.

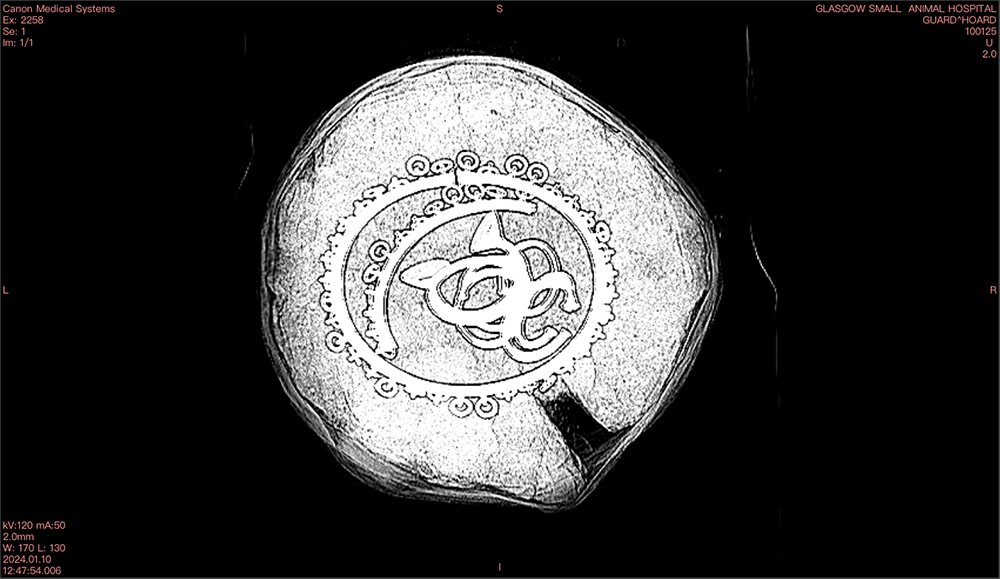

During the excavation, the GUARD Archaeologists recovered an enamelled bronze brooch from the bottom of the foundation trench that held the timber palisade in place. What made this find unusual was that it was not local but was of a distinctly Roman origin.

‘This exotic brooch and others like it typically date to the late second century AD, and are most commonly found along the borders of the Roman Empire, in eastern Gaul, Switzerland and the Rhineland,’ said Jordan Barbour, who co-authored the report. ‘Their distribution pattern suggests that these brooches were particularly popular among members of the Roman military forces, so it’s likely that it came north of Hadrian’s Wall on the cloak of a Roman soldier tasked with garrisoning the Empire’s northernmost frontier.’

What makes this artefact all the more interesting is how it was used by the Iron Age inhabitants of this settlement. There was no evidence that it had been worn by a local Briton. Instead, they had buried it as a foundation deposit, a votive sacrifice of sorts, when constructing the timber palisade around their roundhouse.

‘It’s difficult to say exactly why the brooch was deposited within the palisade trench, but we know that ritualised foundation offerings are observed across many cultures, typically enacted to grant protection to a household, and this is certainly a possibility here,’ said Jordan Barbour. ‘As to how it ended up here, there are a few plausible scenarios. It’s the only Roman artefact recovered from the site. If the inhabitants had established regular trade with Roman Britain, we might expect to find a greater variety of Roman objects, but this is a solidly native context. Rather, the brooch is more likely to have been obtained through ad hoc exchange with Roman troops operating north of Hadrian’s Wall, perhaps even taken in battle as a trophy.’

The Curragh Iron Age dwelling was situated atop a rocky plateau with a steep escarpment acting to deny access from the immediate north, and it may well be the case that the dwelling was sited here and enclosed with a strong timber palisade, due to defensive concerns. Although there were no contemporary Roman forts nearby after the abandonment of the Antonine Wall earlier in the second century AD, an earlier first century AD Roman marching camp some two kilometres to the south-west attests to previous military presence in the area, and conflict between the local Britons and Roman soldiers is likely to have been a recurring element of Rome’s intermittent occupation of south-west Scotland.

This palisaded roundhouse was not the only archaeological feature the GUARD Archaeologists found at the Curragh. The enduring appeal of the plateau was proven by an earlier unenclosed roundhouse that was radiocarbon dated to around the seventh century BC, many centuries before the Romans arrived in Britain. And traces of even more ancient inhabitation were evidenced by the recovery of pottery dating to the early Neolithic period, when a large timber monument was constructed here, between 3,700 and 3,500 BC.

ARO59 A Neolithic Monument, Iron Age Homesteads and Early Medieval Kilns: excavations at the Curragh, Girvan by Jordan Barbour and Dave McNichol is freely available to download from Archaeology Reports Online.

The archaeological work was undertaken by GUARD Archaeology for McLaughlin & Harvey and funded by William Grant & Sons Distillers Ltd. The work was required as a condition of planning consent by South Ayrshire Council who are advised on archaeological matters by the West of Scotland Archaeology Service, who considered there to be a potential for hitherto unknown archaeology to be buried at the site due to the proximity of known prehistoric archaeology.