Centuries-old mystery of Paisley Abbey medieval tunnel is revealed

We already knew Scotland’s finest and best-preserved medieval tunnel lies buried beneath Paisley town centre – but the centuries-old mystery of where it ended had never been solved…until now.

A team of volunteers led by GUARD Archaeologists spent the summer excavating Paisley Abbey’s Drain and found a well-preserved fourteenth century stone archway marking the exact point the drain and its contents once flowed into the River Cart. They established the tunnel – believed to be around 100m long – ends around 3m from the banks of the present-day river, which would have been wider and shallower at the time the drain was built.

And while the find is now being covered up again, the discovery could help lead to a more permanent visitor attraction being built in the future allowing people to go inside the drain.

Excavation leader Bob Will said, ‘We found more than I was expecting and it is really exciting. We found the end of the drain and what was the boundary wall of the monastery. The river was wider and shallower in those days – much more than in the last couple of hundred years, as the walls now surrounding it are artificial. The main parts of the drain date back to the mid-fourteenth century and are incredibly well preserved.’

The Abbey Drain had lain hidden for centuries until it was unexpectedly rediscovered in the nineteenth century, and in recent years, it has been periodically opened up for visitors. There will be an opportunity for the public to put their names forward for a ballot to go inside it during this year’s Doors Open Day in September.

And Bob believes the finds of the past few weeks could help the development of a more permanent attraction opening up a greater degree of public access to the drain. He said: ‘What we have uncovered has helped us see what could be done with any future excavation. We now know much more about the mediaeval ground levels and have a good idea where some of the monastery buildings were. Ideally there would be more permanent access to the drain at some point in the future and what we’ve uncovered here makes that much more feasible.’

Renfrewshire Council leader Iain Nicolson added: ‘Paisley is already on the map as a key visitor destination within Scotland and we are already delivering on ambitious plans to use our unique heritage to drive new footfall to the town centre. We would be keen to explore any opportunities to build on that by opening up more permanent access to the Abbey Drain at some point in the future – and the findings of the Big Dig mean we now know more than ever about this incredible feature beneath the town centre. The Big Dig was a really great community project which has created a lot of interest in Paisley town centre and its history over the past couple of months. We would like to thank our funders for helping make it happen, and all who have been involved in the projects – particularly the local volunteers who came out in all weathers to take part.’

The eight-week Abbey Drain Big Dig was co-ordinated by Renfrewshire Council and led by GUARD Archaeology Ltd, with funding from National Lottery Heritage Fund and Historic Environment Scotland. It also saw a strong community element, with volunteers from Renfrewshire Local History Forum taking part in the dig, students from the University of the West of Scotland filming it, and a series of events and seminars for residents and visitors.

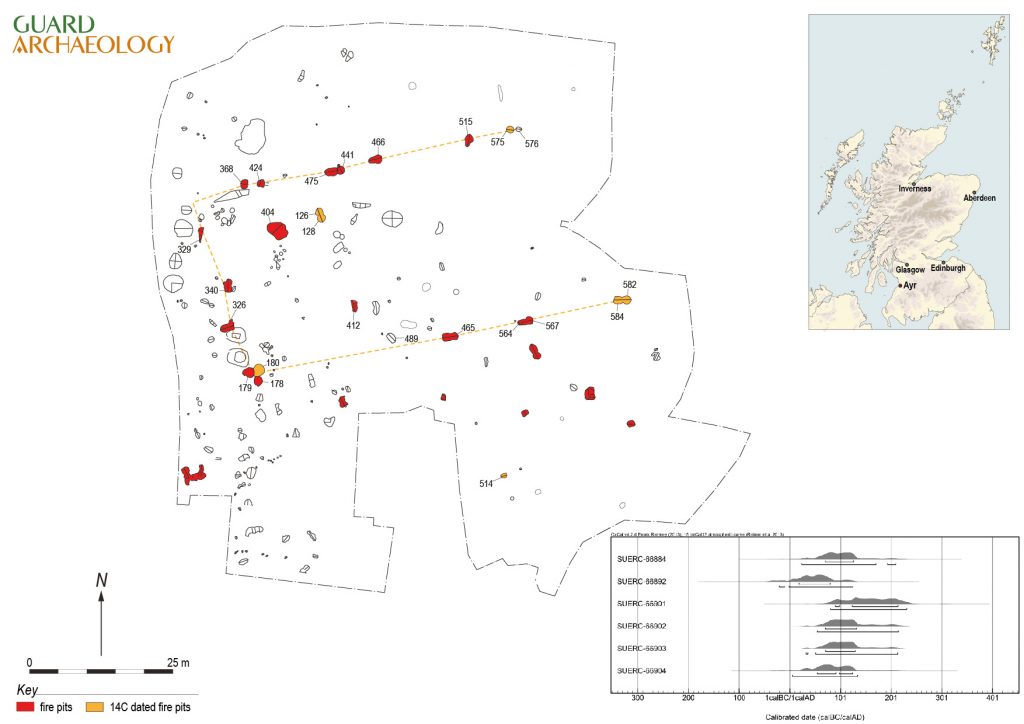

Archaeological investigations coupled with historical research of Newcraighall on the south-east edge of Edinburgh reveal a complex story of land use changes from prehistory to the present day.

Archaeological investigations coupled with historical research of Newcraighall on the south-east edge of Edinburgh reveal a complex story of land use changes from prehistory to the present day. These included various sized coal pits or shafts, and the foundations of four colliery buildings, arranged around a now infilled mineshaft on the southern site. Elements of a designed landscape associated with Brunstane House included a ha-ha that traversed the northern site. The presence of several large culverts may also have connections with both landscape alterations and the coal-mining industry. Fragments of curved and linear ditches appear to be remnants of earlier field systems dating from the medieval and post-medieval periods and associated with extensive remnants of broad rig cultivation found across the two areas.

These included various sized coal pits or shafts, and the foundations of four colliery buildings, arranged around a now infilled mineshaft on the southern site. Elements of a designed landscape associated with Brunstane House included a ha-ha that traversed the northern site. The presence of several large culverts may also have connections with both landscape alterations and the coal-mining industry. Fragments of curved and linear ditches appear to be remnants of earlier field systems dating from the medieval and post-medieval periods and associated with extensive remnants of broad rig cultivation found across the two areas. The historical research demonstrates the complexities of landownership with evidence of the development of coal mining and coal ownership and the social and economic realities of the times. Examination of papers relating to Brunstane House showed that they had direct bearing on the understanding and dating of the landscaping features and other groundworks, including changes to the estate boundaries and the runrig system. A labourer’s diary from the winter of 1735-6 was an especially interesting find from the point of view of what work was undertaken on the estate, by whom and for how much.

The historical research demonstrates the complexities of landownership with evidence of the development of coal mining and coal ownership and the social and economic realities of the times. Examination of papers relating to Brunstane House showed that they had direct bearing on the understanding and dating of the landscaping features and other groundworks, including changes to the estate boundaries and the runrig system. A labourer’s diary from the winter of 1735-6 was an especially interesting find from the point of view of what work was undertaken on the estate, by whom and for how much. Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community.

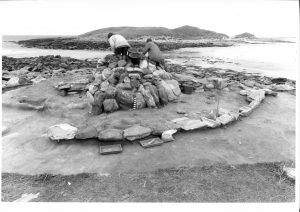

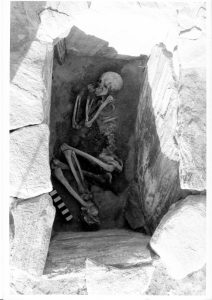

Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community. The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation.

The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation. ‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’

‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’