In 2015, GUARD Archaeology Ltd carried out an excavation in advance of a housing development at Colinhill on the outskirts of Strathaven in South Lanarkshire. The work, which has just been published, revealed two adjacent but distinct Bronze Age roundhouses dating to the mid-second millennium BC and two Neolithic pit groups dating to the fourth millennium BC.

The Neolithic pit groups are indicative of nearby inhabitation. Radiocarbon dates indicate that although the two groups fall broadly within the early and the middle Neolithic (3700–3000 BC), they likely date to either extreme of this and could be up to 700 years apart in origin. The artefactual assemblages present within the pits are typical of those associated within the earlier Neolithic period. These assemblages include a range of Carinated Bowl pottery, pitchstone tools, worked stone tools, axe-head fragments and burnt bone and stone fragments. Both the earlier and latter group of Neolithic pits at Colinhill all comprise un-weathered pits with all but one containing a single mixed deposit, suggesting that the material may have been worked and mixed prior to a swift deposition after the feature was dug. The presence of the two groups around 180 m apart suggest that the upper slopes of Colinhill were sporadically revisited.

The particularly high proportion of pitchstone, which originates from Arran, could be connected to the sites’ proximity to Biggar, which has been previously identified as an area of high pitchstone concentrations. The pottery assemblage also reflects shared attributes of style and technique evident across several Neolithic sites in south-west Scotland. Altogether these provide insight into the exchange of materials and ideas across southwest of Scotland.

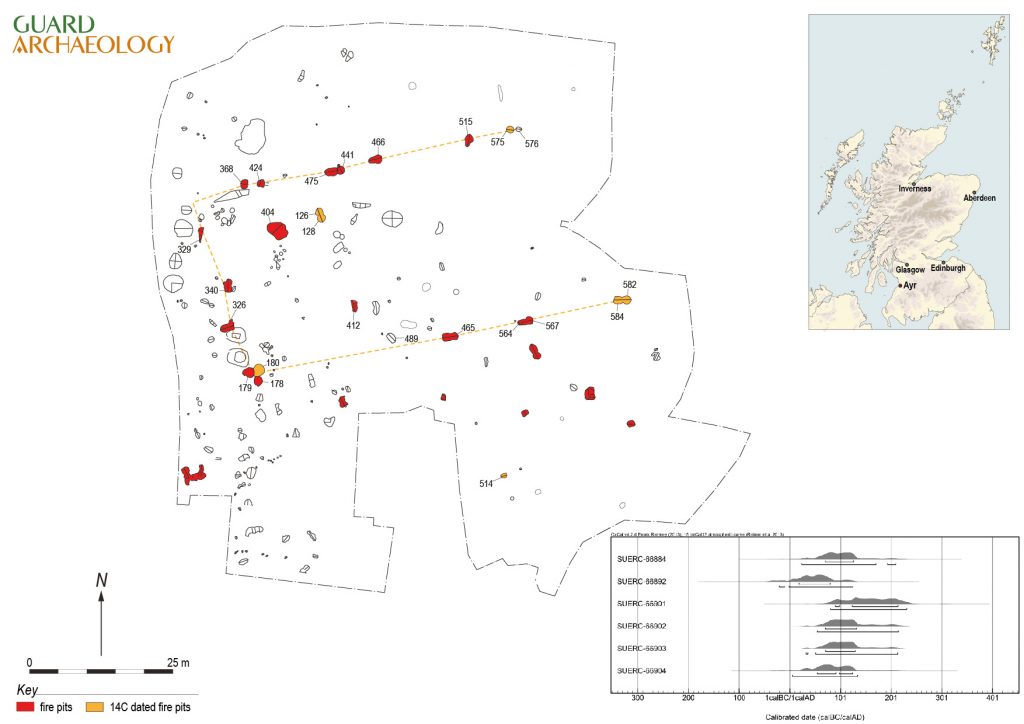

The two roundhouses on the other hand date to around the middle centuries of the second millennium BC – the middle Bronze Age – though it is unclear if they were at any point contemporary with each other. Radiocarbon dating shows that Roundhouse A may have been slightly earlier but there is a possibility that occupation of the two structures overlapped in time. The evidence within both roundhouses for repairs certainly suggests that attempts were made to prolong the life of each structure.

Both roundhouses appear to be typical of a turf or earth constructed ring-bank and post-built structure with east facing entranceways. Given the scale and arrangement of the structure along with the presence of domestic waste material within the post-holes, it seems feasible that both were primarily domestic structures. The 9.1 m diameter of Roundhouse B and 9.5 m diameter of Roundhouse A are also roughly typical of similar structures in western and southern Scotland at this time.

Significantly, both roundhouses share the presence of much earlier Neolithic material. While some of these objects are small enough that they may have originated from the earlier Neolithic activity on the site and ended up unintentionally within the backfill of Bronze age post-holes and ditches; this becomes less likely for the much larger Neolithic objects, leaf-shaped flint arrowhead and a pitchstone core, recovered from Roundhouse B. It seems probable that there was an intentional aspect to the deposition of these objects, which may have been found by the later Bronze Age inhabitants who retained them for their ‘exotic’ form and material. This makes consideration of the lifecycle of these objects particularly interesting, with it being possible that they may have been deposited with a ritual aspect twice, over a millennium apart; firstly, as part of the structured deposition of an early Neolithic Carinated Bowl assemblage from a nearby pit, and then again on their discovery in the middle Bronze Age as part of the roundhouse construction.

The archaeological works were funded by Stewart Milne Homes, Robertson Homes and L S Smellie and Sons Ltd. ARO35: Neolithic pits and Bronze Age settlement at Colinhill, Strathaven by Beth Spence with contributions from Torben Bjarke Ballin, Beverley Ballin Smith and Susan Ramsay, is freely available to download from the ARO website – Archaeology Reports Online.

Archaeological investigations coupled with historical research of Newcraighall on the south-east edge of Edinburgh reveal a complex story of land use changes from prehistory to the present day.

Archaeological investigations coupled with historical research of Newcraighall on the south-east edge of Edinburgh reveal a complex story of land use changes from prehistory to the present day. These included various sized coal pits or shafts, and the foundations of four colliery buildings, arranged around a now infilled mineshaft on the southern site. Elements of a designed landscape associated with Brunstane House included a ha-ha that traversed the northern site. The presence of several large culverts may also have connections with both landscape alterations and the coal-mining industry. Fragments of curved and linear ditches appear to be remnants of earlier field systems dating from the medieval and post-medieval periods and associated with extensive remnants of broad rig cultivation found across the two areas.

These included various sized coal pits or shafts, and the foundations of four colliery buildings, arranged around a now infilled mineshaft on the southern site. Elements of a designed landscape associated with Brunstane House included a ha-ha that traversed the northern site. The presence of several large culverts may also have connections with both landscape alterations and the coal-mining industry. Fragments of curved and linear ditches appear to be remnants of earlier field systems dating from the medieval and post-medieval periods and associated with extensive remnants of broad rig cultivation found across the two areas. The historical research demonstrates the complexities of landownership with evidence of the development of coal mining and coal ownership and the social and economic realities of the times. Examination of papers relating to Brunstane House showed that they had direct bearing on the understanding and dating of the landscaping features and other groundworks, including changes to the estate boundaries and the runrig system. A labourer’s diary from the winter of 1735-6 was an especially interesting find from the point of view of what work was undertaken on the estate, by whom and for how much.

The historical research demonstrates the complexities of landownership with evidence of the development of coal mining and coal ownership and the social and economic realities of the times. Examination of papers relating to Brunstane House showed that they had direct bearing on the understanding and dating of the landscaping features and other groundworks, including changes to the estate boundaries and the runrig system. A labourer’s diary from the winter of 1735-6 was an especially interesting find from the point of view of what work was undertaken on the estate, by whom and for how much. Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community.

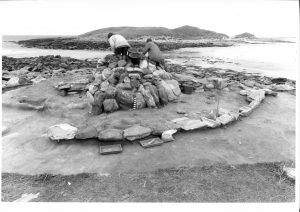

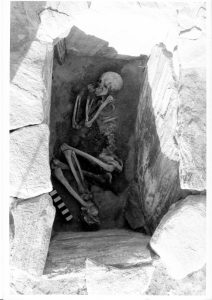

Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community. The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation.

The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation. ‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’

‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’