Newly published research reveals how GUARD Archaeologists discovered the remains of a hitherto lost village and the secrets it held.

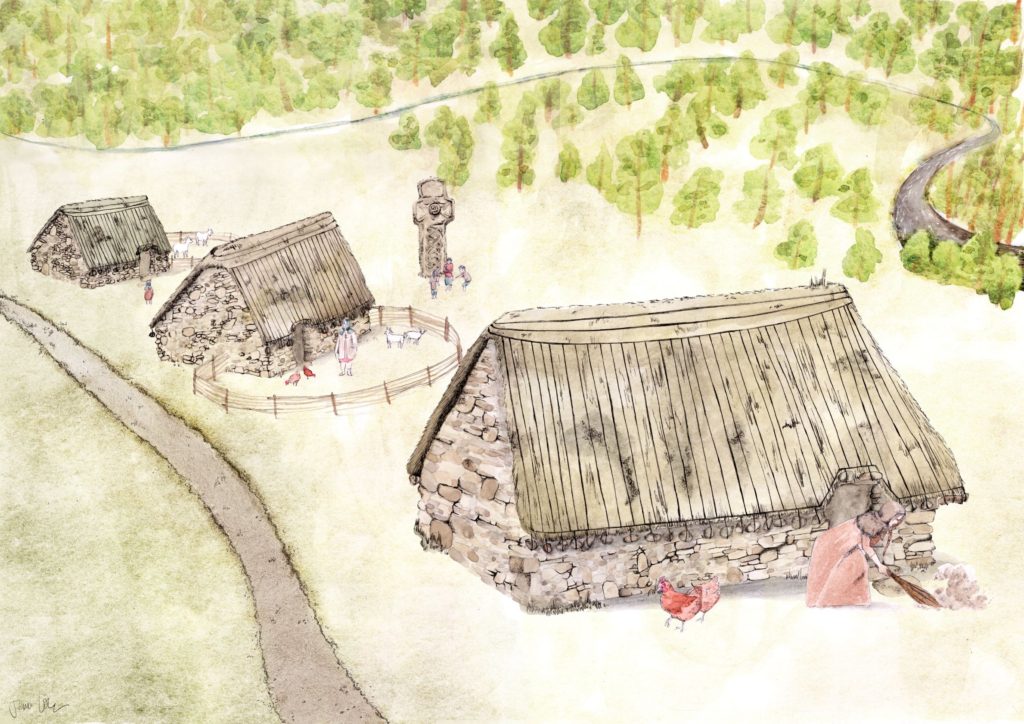

As part of the M8, M73 and M74 Improvements, Transport Scotland and its consultants commissioned GUARD Archaeology to undertake archaeological investigations. At one of the sites, where the tenth century Netherton Cross stone once stood, the archaeological remains of four medieval houses were discovered along with pottery, gaming pieces and other objects. Remarkably, these remains survived literally on the edge of the existing hard shoulder of the M74.

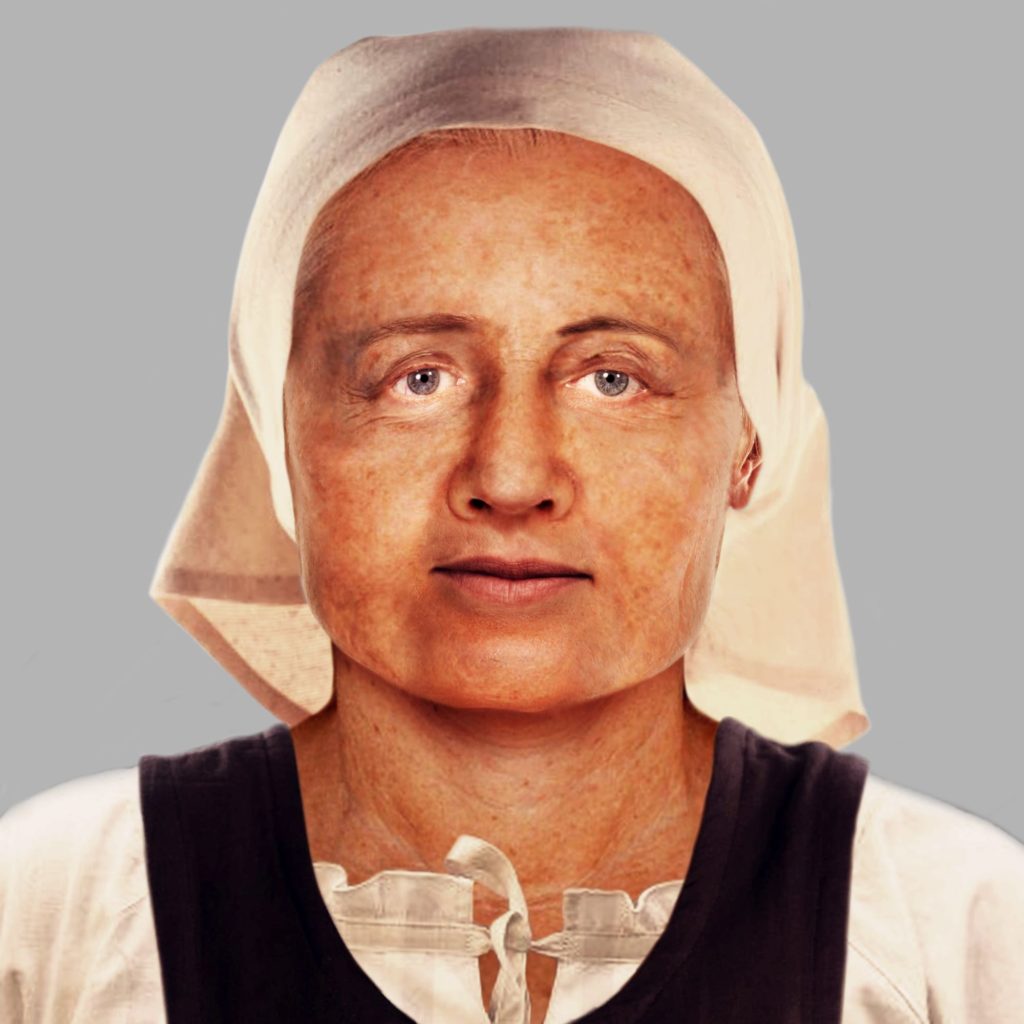

The remains of four stone buildings were revealed during the excavation. Radiocarbon dates suggest that the village dated to between the beginning of the fourteenth century AD and the first quarter of the seventeenth century AD. Finds included pottery sherds, mainly from jugs as well as cooking pots, storage jars and bowls, which date to this period too. There was also metalworking debris providing valuable evidence of iron smelting, bloom refining and probable blacksmithing in the village. Most of the metalwork itself recovered during the excavation comprised various forms of nails and other common fittings that one might expect to find in a normal settlement.

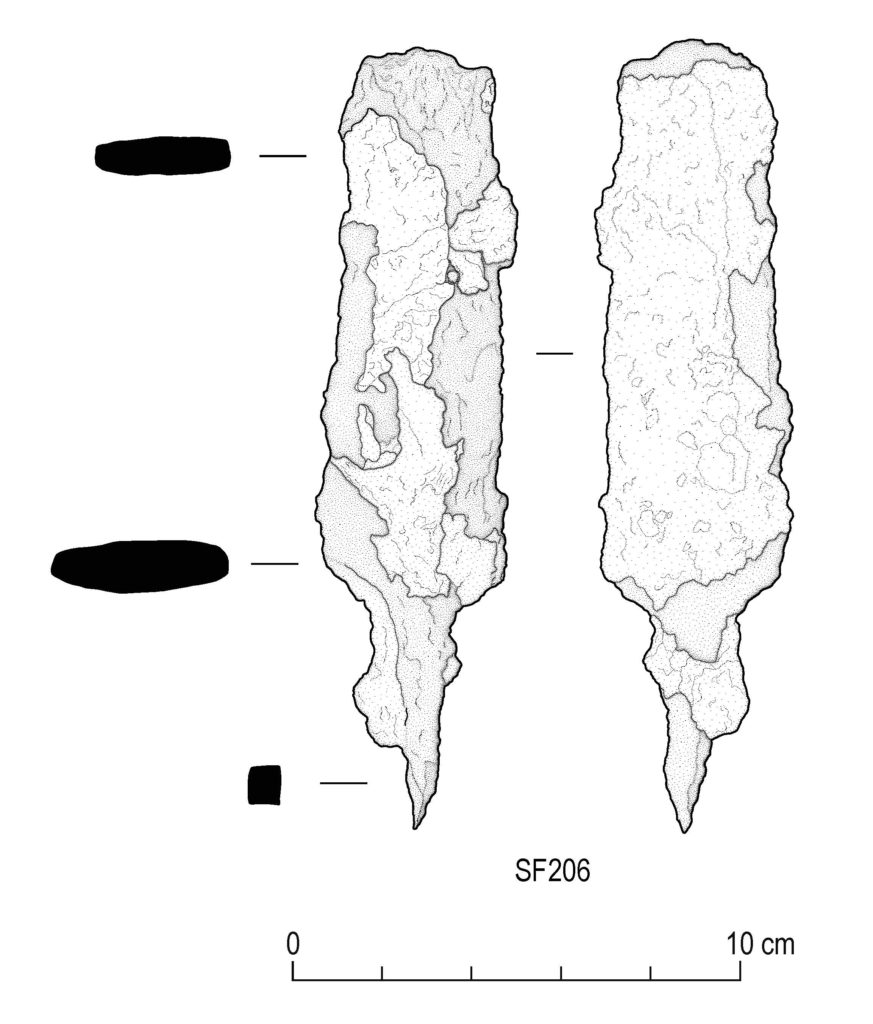

But one of the buildings yielded an unusual deposit of artefacts within its foundations. Amongst the more recognisable occupation debris of pottery sherds was a collection of objects not found elsewhere across the site. This included a whetstone of fine-grained sandstone, a spindle whorl made of cannel coal, a gaming piece or counter crafted from a sherd of green glaze pottery, and two seventeenth century coins. The final artefact was an iron dagger.

‘Mineralised organic material on its blade suggests it was sheathed when buried, and that it was probably intact and still useable at that time,’ said Gemma Cruickshanks of National Museums Scotland, who analysed the metalwork. ‘The form of this dagger is indistinguishable from Iron Age examples, indicating this simple dagger form had a very long history.’

The practice of depositing special objects in medieval and post-medieval buildings is well documented and was a ritual performed to protect the building and its inhabitants. In this case there appears to have been a deliberate selection of objects placed here. While the whetstone, whorl and gaming piece are distinctly domestic objects with a practical purpose, they may also have represented a personal connection to an individual, activity, or place that would make them special to the occupants. The dagger’s potential antiquity as a prehistoric object perhaps lent it a quality of otherness. Reuse of prehistoric objects as depositions in medieval settings has been recorded in excavations of medieval churches in England, and flint arrowheads were traditionally identified as ‘elf-bolts’ and long recognised for their malevolent magical properties.

‘The special or talismanic qualities of this dagger as a protective object may have enhanced the ritual act to protect the household from worldly and magical harm,’ said Natasha Ferguson, another of the co-authors. ‘The deposition of these objects under the foundation level of one of the houses may have been intended to affirm this space as a place of safety for them and generations to come.’

Alas, it did not seem to work. The village of Netherton was swept away in the eighteenth century by improvements to the estate by the Dukes of Hamilton, transforming the site into well-ordered and symmetrical parkland with wide avenues and enclosures. And then later came the motorway, which subsumed most of the village; the four stone structures encountered during excavation represent the last vestiges of this lost village.

The archaeological work was funded by Transport Scotland. ARO41: The road to rediscovery: Netherton Cross and the M8, M73, M74 Motorway Improvements 2014-15 by Iraia Arabaolaza, Warren Bailie, Morag Cross, Natasha Ferguson and Kevin Mooney is freely available to download from the ARO website – Archaeology Reports Online.